How a Photoelectric Sensor Saved My Job

Larry Bush

I owe it all to a Photoelectric Sensor

In 1996 I was employed as maintenance supervisor at an olive cannery in the heart of California’s fertile San Joaquin valley. We were restarting the cannery after an extended shutdown while the cannery changed owners. This was my first opportunity to work in the food industry and a cannery. There were issues for me to learn and learn fast. The new harvest season’s olives were due to start arriving just four weeks after I was hired.

Only four of the previous maintenance personnel were available to be rehired, so things were looking a little bleak at times. None of the new mechanics or electricians had food industry experience, either. In addition, there were almost no blueprints or wiring diagrams for the entire cannery or processing plant.

However, on the scheduled startup day, everything ran. Our two main can lines used Angelus 60L Seamers with a maximum output capability of 600 cans per minute. That figures out to ten cans per second. That’s faster than I can count. The Seamers seal the end cap onto the cans. Due to space limitations, new, spiral elevators had been designed and added by the previous owners. The elevators and controls had been wired up but they never ran prior to shutdown.

We started up slow, but problems immediately surfaced. The discharge line from the spiral elevator to the cooker was a plastic cable line. Cans could tip over and jam. When the can jam-up backed cans into the discharge from the spiral elevator and then round and round the elevator. It took a considerable effort and time to remove the jammed cans from the elevator.

A photoelectric sensor with a reflective lens was installed on the discharge cable line about six inches from the can entry to the discharge cable line. This sensor was designed and connected to stop the seamer and elevator when a jam-up occurred. The sensor had to see an opening between the cans, operate on/off, or it would shut down the elevator.

It turned out that the photoelectric sensor could only be adjusted to stay on all the time or off all the time when the cans were going by at any higher rate than Jog speed on the Seamer. We adjusted and adjusted the sensors. The sensors were replaced with new sensors. It did no good. The lines were stopped while we traced all the control and power wiring so we could try to determine if there was a problem in the wiring.

When I looked around, the Plant Manager, accompanied by the company President, Vice President and the Financial Controller were standing to the side watching me. All four of them had their arms crossed and unreadable expressions on their faces. I knew I was in trouble and had to get on top of this problem in a hurry.

Finally, I determined that the previous engineer had ordered an incorrect application for the original photoelectric sensors. Performing my own can lines engineering, I looked up the specifications for the installed sensors and found that their response time was not fast enough to “see” the cans as they went by. I looked in an Allen-Bradley sensor book for a photoelectric sensor with a fast response time, able to withstand the harsh environment of a cannery (steam and water), and would continue operation even when subjected to lots of vibration.

The photoelectric sensor I decided on was the Allen-Bradley Series 4000B Bulletin 42RL. This sensor has a response time of 5 milliseconds. That time was faster than our requirements. The case of the sensor is designed for harsh environments and kept the steam and wash-down water from entering the delicate, control circuitry area of the sensor. The vibrations from the elevator and the cable line had no effect on the solid state wiring of the sensor.

After installation, the sensor was connected and pre-adjusted for the can stream. The sensor kept the cable line and elevator running and was “seeing” the individual cans. We physically simulated a jam-up of cans on the cable line. When the cans backed up to the sensor, the sensor operated and shut down the spiral elevator and opened the clutch on the seamer, stopping line production.

There remained only some fine tuning of the sensor as we ramped up to top speed of between 550 and 570 cans per minute. Again, we had a “command” audience of the top company officers for our startup. When the lines started and continued running or stopped on a can backup with no corresponding elevator jam, there were smiles all around. My job was safe.

Most of the can jams on the cable line were reduced to acceptable levels by the work of the Cookroom Manager and his Seamer Operators/Mechanics. They reworked the can drops and built-in several can cutouts. The can cutouts are places where a can lying on its side will be ejected from the cable line, thereby eliminating an almost certain jam in a can drop or at the Cooker entrance. By reworking the can drops, can jams in the drops were almost totally eliminated.

Besides the fact that I kept my job, I learned that anyone can make a mistake and, when in doubt, check the factory specifications of the equipment you are working with.

Larry Bush has been an electrician for 47 years, and in maintenance management for 22 years. Download a sample of his new e-Book: Maintenance Policy and Procedures Manual!

Related Articles

OEE: Overall Equipment Effectiveness

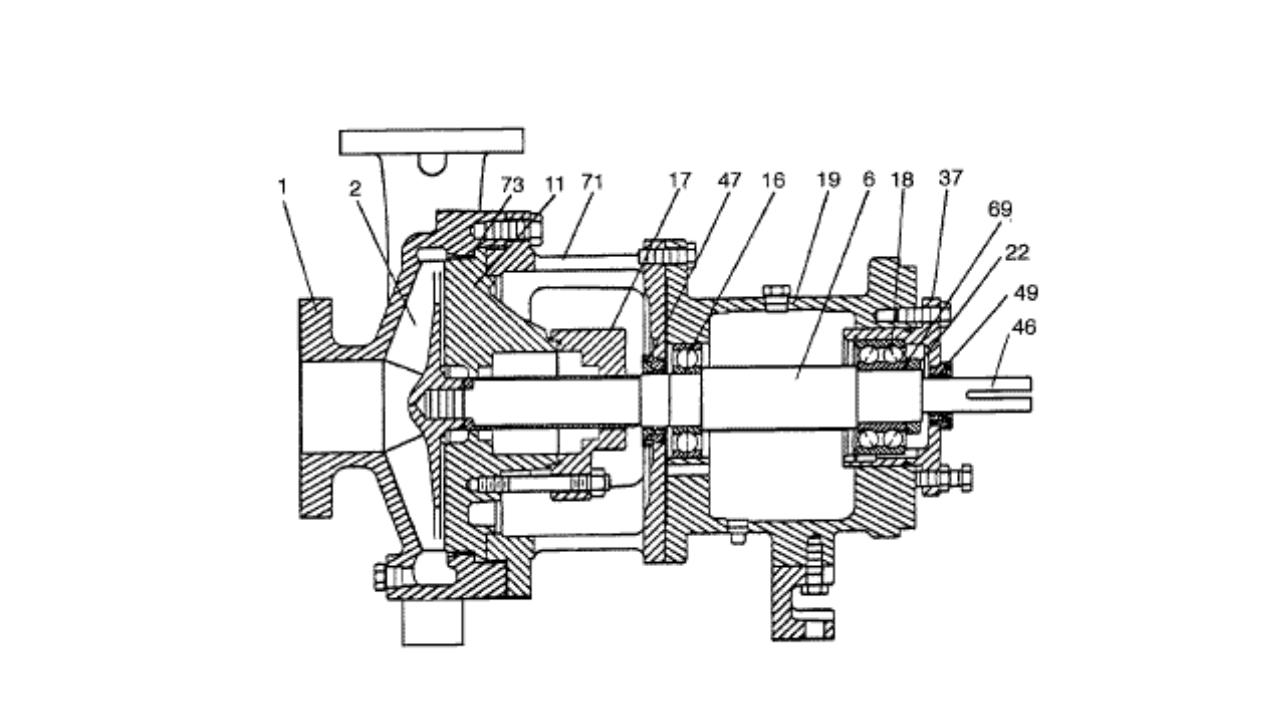

What the Pump Was Designed to Do and Why it Doesn't Do it

What is Wrong with the Modern Centrifugal Pump?

Digging Up Savings: Go with the Flow

Chain Drive Design Recommendations

Classifying Chemicals to Assure Effective Sealing