Best Practices in Lubrication

Kevin Campbell, Plant Engineering

Lubrication is Important

Like blood coursing through the veins of living beings, lubrication is what keeps a plant’s capital investments operating smoothly and efficiently. At the same time, when lubrication becomes contaminated or depleted of its sustaining properties, overheating or exhaustion are among the problems that can occur. That leads to downtime and loss of production, and the potential of some hefty maintenance expenses.

So what should be done to keep your plant’s machinery effectively lubricated? There’s no universal right answer, but experts interviewed by PLANT ENGINEERING said that if you’re not careful, plenty of wrong ones are out there to choose from. These experts offered their ideas on what considerations should — and should not — be made when establishing an effective lubrication program.

It’s all in the Practices

“I think the key thing for a good lubrication program is to increase or maximize component life while monitoring and maximizing lubrication life,” said Mike Galloway, senior lubrication engineer for ExxonMobil Corp. “Once you establish a good lubrication program, it’s astounding how many dollars you can save, with regards to identifying problem areas or misapplication areas or issues like that.

The first step, according to Galloway, is to identify every point of application. What oil is recommended for the application? How should it be applied, and how frequently should it be checked and changed? “They say the number one failure, when you’re talking about lubrication, is putting the wrong oil in the wrong application,” Galloway said.

Once the lubrication and its handling procedures are established, the next step is to route the lubrication so that there’s some type of maintenance practice. A procedure needs to be in place that specifically states how often the engineer needs to go and check or change the oil.

After you’ve identified that process, the third step, Galloway said, is to train your personnel so that they understand the fundamentals of oils. They need to know why specific oil is right for the specific application.

“You don’t intertwine or mix those. It’s so much common practice in plants these days that oil is oil, and as long as you apply one oil, you’re fine,” Galloway said. “But in so many cases, where you just put oil in, you’re going to have a failure or a problem.”

Analysis is a Crucial Step

The essential step to a good, ongoing lubrication program is oil analysis. “Have a good, solid oil analysis program that can be routinely polled for trending of critical pieces of equipment,” Galloway said.

According to Galloway, the oil analysis should be based on two parts. First, it should focus on the oil itself, specifically, its condition. Second, the analysis should look at the condition of the equipment.” Galloway likens the procedure to visiting the doctor for a blood test.

“It’s like when a doctor takes a blood sample from you. He can forecast from it how you’re health is. That is essentially what the oil analysis is doing for the equipment,” Galloway said.

However, testing needs to take place before something goes wrong. At that point, it’s too late.

“You want to start to sample a unit on a trending basis and do that periodically, whether it is monthly or quarterly,” Galloway said. “And those are things to establish around a lubrication program, tying it in with other preventative maintenance practices, and you can really narrow down the failure rates. At least you can catch the cash-dropping failures that could be happening, that could be unexpected. That’s what kills you on downtime.”

Proper Storage is Important

Not to be forgotten are good storage and handling procedures. How, and particularly where, lubricants are stored can have a substantial impact on their performance.

“I recently went into an account where there had been some differences that happened with regards to our distributor and delivering. When I arrived, the client was convinced that we had delivered them water. They had three tote bins, two outside, one inside, and they claimed there was water in everything.” Essentially what happened, Galloway explained, was that, as water collects on top of a drum (or in this case, a tote), even if it’s sealed, as the drum heats up during the day, it will actually blow gases through the seal. The reverse happens at night – as the drum cools down, it will suck in whatever is around that seal, including water.

“When I pulled the samples, the water was killing their bearings,” Galloway said. “And this is a system that runs 3,600 RPMs. Any amount of water that gets mixed in with that oil will absolutely fail that bearing. And two of the three tote bins were just full of water, which you could see, right on top.”

This is not to say that lubricants cannot be stored outdoors. “You’ve just got to take some precautions,” Galloway said. “Put them underneath some type of shelter, like an awning. Because if they’re outside, you need to make sure that the bungs are not exposed. You need to cover them or put them on their side, such as they don’t collect water on the top. Those are the key things.”

Yet another critical consideration is filtration. Without it, users not only reduce the useful life of their equipment, but also the useful life of the lubricant itself.

“In the last two to three years, my focus has really been explaining to people that, even though you can’t see them, there are abrasive components that get into your breathers. And not only in your storage facilities, but you need to filter the oil from one container to the next until you get it into the actual end-use component. And then you have to filter again through that process.” Galloway said. He added that pump life is significantly reduced by not filtering. “Filter data suggests that a standard pump will run two years unfiltered, as opposed to 14 years when filtered to a certain micron rating.”

Once all of that is established, a routine audit is very helpful, Galloway said. You’ll want to do a walk-through audit, which provides another set of eyes on the oil processes and allows you to talk to the oiler or the operations guy, whoever is oiling the systems, and ask them how they do that. It allows you to monitor the process. You need to have some type of auditing system that recovers what your processes are, he said.

Lubricating the Right Way

“It’s all about uptime and making sure equipment is available when it’s needed,” said Brian Richards, VP of sales and engineering for Vogel Lubrication, Inc., Newport News, VA.

What Richards stresses is the installation of an automatic lubrication system. Such systems are designed to ensure that the correct amount of lubricant is applied to machinery at the correct intervals, and they remove an element of variability that can result from manual lubrication practices.

“When we go in with a customer, it’s to ensure machine reliability through taking a lot of the operator error or the poor maintenance practices out of the equation for things like machine uptime and machine durability,” said Robert Aman, president of Vogel. “It’s better to have a small amount of grease going in on a very frequent basis as opposed to over-lubricating, and then not lubricating again until after it’s dry, and then over-lubricating again.”

Incorrect machinery lubrication can cause a variety of problems, Richards said. Over-lubrication can cause blown seals and big messes, and these scenarios lead to additional problems.

“When you over-lubricate, dirt can collect where that lubrication is. Then, as it starts to heat up, who knows where that dirty lubrication flows? It could be a way that you’re introducing dirt back into whatever it is that you’re lubricating,” Richards said.

When it comes to under lubrication, Aman continues, “you have accelerated wear, typically. Before the machinery gets to any freezing up, you’ll have more wear, you’ll have a lot more stick slips happening, where things just aren’t moving as smoothly.”

Before implementing any kind of lubrication system, manual or automation, Richards and Aman suggested, cost and logistics must be considered.

“Obviously, there is a cost to a good lubrication system, and that is you have to be spending money on lubricant,” Richards said. “You don’t go out and spend $200,000 on a machine tool and then don’t take care of it. There’s also a hardware cost, and in our case, it’s not like just putting a fitting on something, leaving a manual and then telling someone to go do this every day or week or whatever the frequency would be.”

Consider the Logistics

The logistics of a lubrication program present almost as many aspects to consider as does the program itself.

“First and foremost, it’s something that needs to happen at the time when you’re setting up new equipment,” Richards said. Implementing a lube program with older machinery, even a purchase as recent as within five years, can prove challenging, he said. “You’ll have a harder time being able to ensure the benefit of the program because of damage that could’ve happened to the machine earlier in its life,” Richards said. “We recommend getting into this early and setting up a good program from an early stage.”

Machine visibility and access are other factors to consider. “You need to be able to refill reservoirs and such, but you also need to be able to easily inspect it and monitor its performance.”

Monitoring the lubrication program is also a significant aspect, and Richards described a couple of different methods to accomplish it. In a circulating system, users pass lubricant from a large tank through whatever it is that needs lubrication. The used lubricant then returns to the tank, where it is conditioned and sent back through the machinery.

“When it comes to monitoring on a circular system, we can monitor the quality of oil and the loss of oil very easily,” over a period of time, Richards said. “If you have one drop happening every minute in a spot, you will eventually see a difference in the level of the reservoir,” he said. However, it’s difficult to measure how much lubricant is lost over a one-day period of time.

“The advantage of using a total-loss system is the fact that, if you know that you’re running at a certain speed and you need to lubricate a certain amount, then you know what the consumption should be and you’ll know if you have a problem if you’re not consuming that amount,” Richards said. Other monitoring systems that measure machine performance, vibration and temperature can also be good indicators to the performance of the lubrication program.

Best Practices in Lube Storage, Management

Managing a lubrication program is more than just finding the right oil. It also means managing that oil from delivery to storage to program management. Ted Naman, Technical Services Product Coordinator, ConocoPhillips Lubricants, Conoco Brand, discussed some of the storage and lubrication management issues with PLANT ENGINEERING .

Q: There are new technologies that replace the 55-gallon drums for fluid storage on-site. What are the pros and cons of both types of fluid storage?

A : The most common replacement technology for 55-gallon drums in the plant is totes. Plastic totes are available in different sizes and configurations. Their main advantage over 55-gallon drums is they can hold anywhere from 5 to 10 times the amount of fluid. They are self-sufficient, with their own pumps, filters and valves, and can be returned to the supplier or exchanged for another tote of similar size. They can be skid-mounted or placed on rollers for easy movement within the plant, and the fluid lasts for a long time before re-ordering.

Their disadvantage is their physical size, which in smaller plants can limit their movement within the plant. They are also dedicated for one particular fluid, so no commingling with another fluid can take place.

Q: One issue for plant managers is to squeeze all the product out of a storage unit of any size or configuration. This is especially true today with any petroleum-based product. What are some best practices or tips in this area?

A : Segregate petroleum products by type. For example, anti-wear hydraulic oils, gear oils and circulating oils of different viscosity grades and container size can be consolidated into one or two products using totes or bulk tanks. Greases can be ordered in 35-lb pails, 400-lb kegs or totes for use in centralized lube systems. Coolants and chemicals can also be stored in similar size containers.

Q: What are some of the issues customers come to you with, and what are some of the solutions you recommend?

A : Most of the issues we address are lubricant-related and not package or container related, such as product recommendation for a specific application, cross-referencing to competitive products, and assisting with Lube Surveys at the plant.

Q: Do synthetic products present any special challenges in fluid handling?

A : Yes they do, in the fact they have to be segregated for specific use, and they cannot be mixed with other lubricants. Also, synthetics generally are not available in small containers such as 5-gallon pails. The most common package is a 55-gallon drum.

Q: Are there any innovations that plant managers should look for in the coming couple of years?

A : In my opinion, the next innovation on the horizon for plant managers is computer-controlled or automated inventory and distribution of petroleum products and chemicals in their plants, where inventory is automatically replenished based on demand.

Synthetic Lubrication Guide, Filtration Information on the Web

PLANT ENGINEERING ’s exclusive guide to synthetic lubricants is newly updated for 2006 and now available for viewing and download on the Website at https://www.plantengineering.com/

There you’ll find a side-by-side comparison on the most popular weights, grades and types of lubricants, all organized by ISO viscosity grade. Information on extreme pressure gear oil, high-pressure hydraulic oil and compressor lubricants are among the products for review. To download the Synthetic Lubrication Chart, go to

Check out the following sources on the Web: https://www.plantengineering.com/

Dow Corning offers training courses on best practices in lubrication for operators, technicians, managers and supervisors:

Kyle Jeffers, a machinery management specialist for Bentley Nevada Corporation, takes an in-depth look at the types of lubrication, additives and more that goes into a lubrication program at

Kevin Campbell, Senior Editor at Plant Engineering

Related Articles

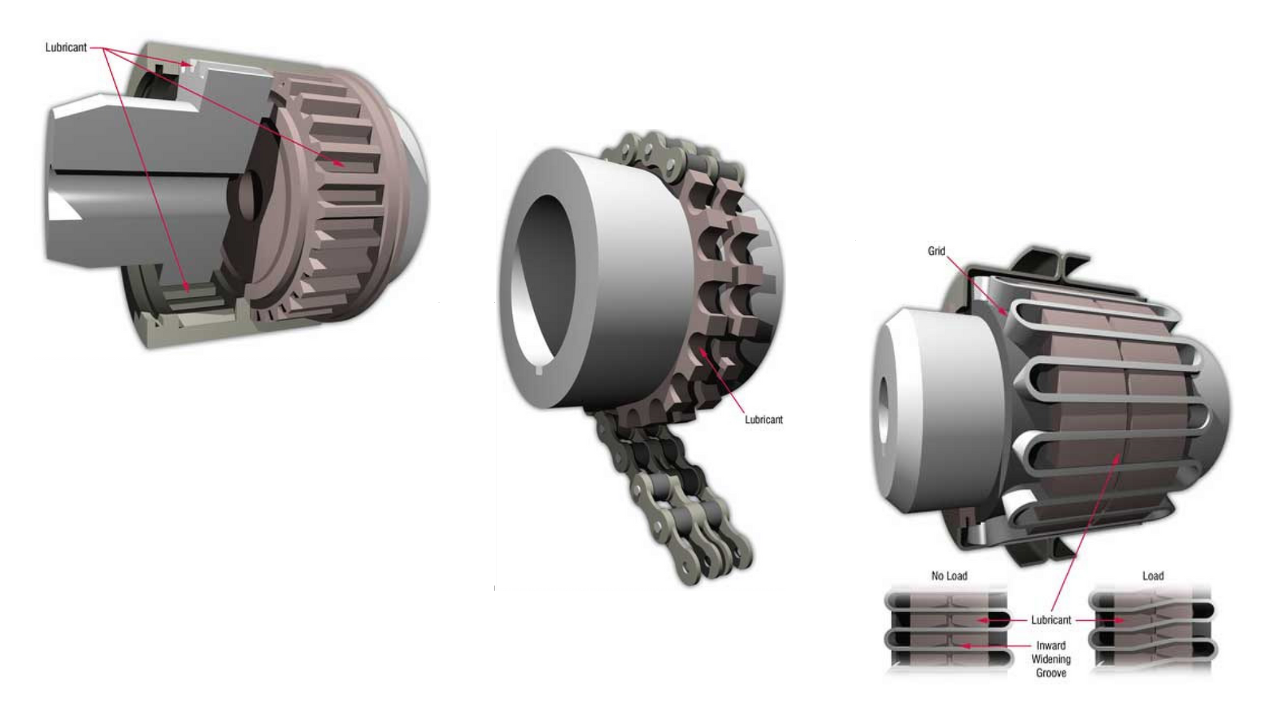

The Lubrication Requirements of Couplings

The Building Blocks to Creating an Effective Lubrication Program

Does Lubrication Belong in the CMMS?

Water Contamination

Ultrasound for Better Lubrication

Top Ten Ways Not to be World Class at Machinery Lubrication