The Importance of Minimizing Corrosion Product Transport to Steam Generators (Part 4)

Brad Buecker, SAMCO Technologies and Buecker & Associates, LLC

Posted 11/4/2025

Introduction

Minimize Corrosion Product Transport to Steam Generators: In the previous installment of this series, we examined modern chemical treatment programs for steam generators. At the high temperatures and pressures in boilers, well-operated and maintained chemical feed systems are critical for preventing corrosion. However, the task becomes more challenging if corrosion products from other areas of the system travel to and deposit on boiler tubes. The chemistry beneath deposits can be quite different than in the bulk boiler water, sometimes resulting in severe corrosion.

The Influence of Corrosion Product Deposition in Boilers

Carbon steel is the typical material of construction for boilers. (The superheaters/reheaters of high-pressure units require higher alloy steels.) With good feedwater and boiler water treatment, carbon steel will develop a protective oxide layer. This is either magnetite (Fe3O4) in industrial units or ferric oxide hydrate (FeOOH) in modern utility units. (Specifics of this chemistry may be found in references 1-3.) These oxides develop naturally to form a relatively uniform layer.

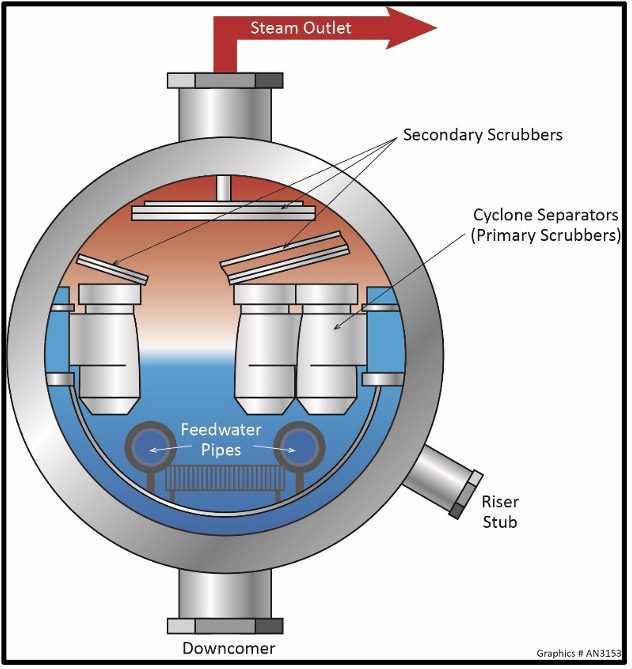

Now consider how, and what can happen when, corrosion products enter the boiler. Industrial plants may literally have miles of carbon steel piping bringing back condensate from steam-fed heat exchangers to the boilers. Multiple such systems often exist at large facilities. The large majority (>90%) of carbon steel corrosion products are iron oxide particulates, with only a small amount of dissolved iron as the balance. Iron particles that reach the boiler will deposit on boiler internals, with precipitation usually concentrated on the hot side of boiler tubes. The porous deposits present more than one problem. For starters, deposition degrades heat transfer, which requires increased boiler firing to achieve the necessary steam output. Furthermore, restricted heat transfer increases the fireside temperature of the tubes, and this can lead to tube deformation and reduced life expectancy.

Even worse problems may occur, and especially in high-pressure boilers, on the waterside.

Boiler water penetrates the deposit through various channels. As the water approaches the tube surface, temperatures increase. The water boils off, leaving other chemical species behind. This phenomenon is known as wick boiling. A condenser tube leak in a high-pressure steam generator offers a dramatic example of what can happen via wick boiling. Cooling water from a lake or river may contain up to several hundred parts-per-million (ppm) dissolved solids, primarily the cations, calcium, sodium, magnesium, and potassium; and the anions, bicarbonate, chloride, silica, and sulfate. (For plants that use seawater for cooling, this water, of course, has vastly higher concentrations of dissolved solids.) These elements and compounds can initiate a number of scale and corrosion reactions, particularly at the high temperatures in the boiler. The equation below outlines a common and quite troublesome reaction that can occur under deposits.

As is evident, a product of this reaction is hydrochloric acid. While HCl causes direct corrosion, the reaction of the acid with iron generates atomic hydrogen. The extremely small hydrogen atoms penetrate into the steel and react with carbon atoms to generate methane (CH4):

Formation of gaseous methane and hydrogen causes cracking, greatly weakening the steel’s strength. Hydrogen damage is very troublesome because it cannot be easily detected. After hydrogen damage has occurred, the plant staff may replace tubes only to find that other tubes continue to rupture.4

The opposite situation can occur if the boiler water treatment program generates excess caustic alkalinity (NaOH). Caustic can also concentrate under deposits and attack the boiler metal and protective oxide film via the following reactions:

This attack is usually much more pronounced in high-pressure boilers. Modern guidelines recommend a caustic upper limit of 1 ppm in utility units.2

In steam generating systems that have heat exchangers with copper alloy tubes or plates, copper corrosion product transport may cause difficulties. Copper is cathodic to carbon steel and can deposit on boiler tubes. Galvanic corrosion is a likely result. A difficulty that plagued the power industry, particularly in large coal-fired units constructed in the last century, was transport of copper compounds to steam turbines. Many of these units had feedwater heaters with copper alloy tubes due to the excellent heat transfer properties of the alloys. Above 2000 psi or so, copper corrosion products carry over vaporously to steam and deposit on turbine blades. Even a few pounds of copper can seriously degrade turbine efficiency. This issue has mostly disappeared due to the replacement of coal-fired units with renewable energy and combined cycle power plants. The heat recovery steam generators (HRSGS) of combined cycle plants typically have no copper alloys in the system.

Corrosion Product Minimization, The Root Cause Approach

For many industrial boilers, sodium softening by ion exchange is sufficient to minimize boiler water scaling potential by removing hardness ions, i.e., calcium and magnesium. However, with sodium softening only, all other dissolved solids will travel to the boiler. This includes alkalinity, usually in the bicarbonate form (HCO3–). Bicarbonate, upon reaching the boiler, is in large measure converted to CO2 via the following reactions:

The total conversion of CO2 from the combined reactions may reach 90%. CO2 flashes off with the steam, and when the CO2 re-dissolves in the condensate, it will increase the acidity of the condensate return.

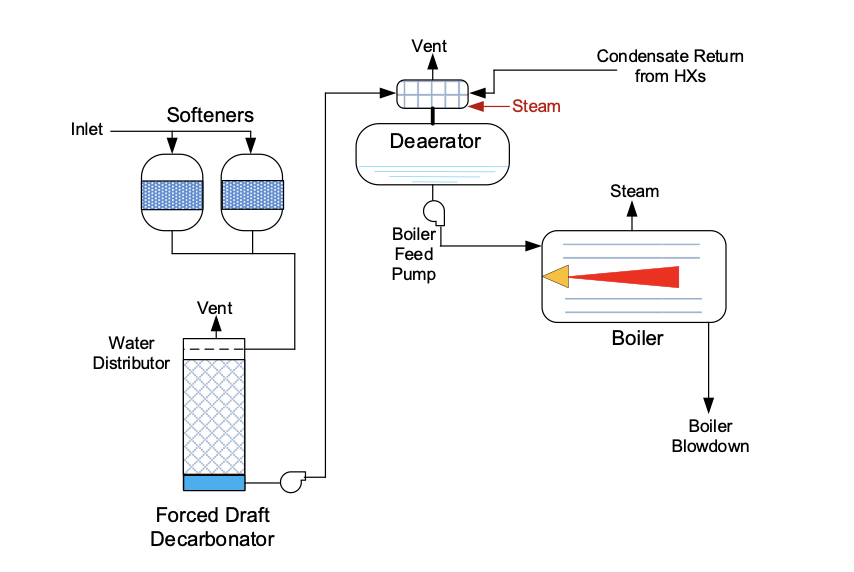

Accordingly, many sodium softening systems are often followed by a decarbonator or perhaps a split-stream dealkalizer to reduce alkalinity to low ppm levels. The fundamental chemistry in either process converts the alkalinity back to carbon dioxide, which is then extracted from the treatment system.

An alternative makeup treatment method, which has become standard in the power industry as part of high-purity makeup systems, is reverse osmosis. RO is now gaining popularity for industrial makeup water treatment. Modern RO membranes can remove 99% or more of all dissolved impurities and thus may be very attractive for some applications.

The reduced dissolved solids loading in the boiler can also reduce blowdown requirements.

Oxygen

Dissolved oxygen (D.O.) exhibits the most destructive potential of all “natural” condensate system corrodents.

Besides generating products that travel to steam generators, oxygen corrosion can greatly reduce the life expectancy of condensate return piping. The author once joined a facility where oxygen corrosion of a closed cooling water system had produced leaks so severe that it was impossible to maintain corrosion protection chemistry. Significant piping repair and replacement were necessary to return the system to normal operating conditions.

Dissolved oxygen can be corrosive to copper alloys, particularly in the presence of a complexing agent such as ammonia. D.O. will oxidize the normally protective cuprous oxide (Cu2O) surface layer to cupric oxide (CuO), which will then gradually dissolve in water containing ammonia. (The author assisted with projects to reduce this corrosion on the steam side of copper alloy steam surface condensers.)

The root cause solution is to find and seal spots that allow air/oxygen to enter condensate systems. These locations or mechanisms include, “vented receiver tanks, [and where] air is drawn in through small leaks [if] the system is under a vacuum or operates intermittently and pulls vacuum as equipment cools, [with in-leakage points such as] threaded joints, heat exchangers, faulty steam traps, and packing glands.”7

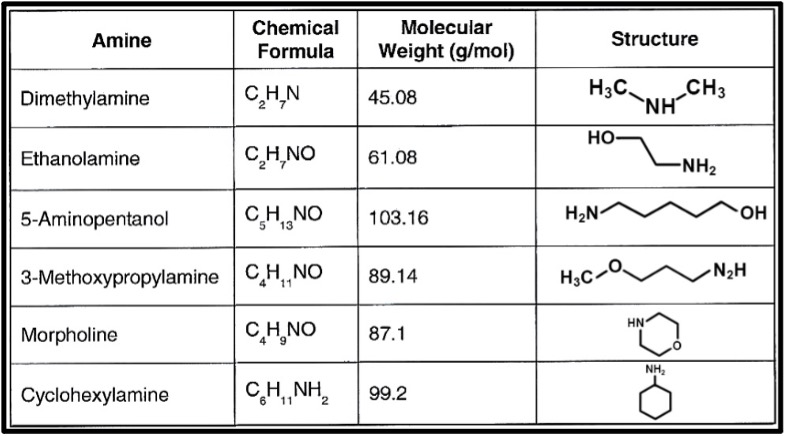

Within the steam generator network, almost without exception for industrial boilers is the use of mechanical and chemical deaeration to remove oxygen from the feedwater. A properly designed and operated deaerator should reduce D.O. concentrations to 7 parts-per-billion (ppb), with additional removal by compounds such as carbohydrazide. Another important factor in minimizing general corrosion of steel is maintaining a mildly alkaline pH, approximately within a 9-10 range. For lower-pressure industrial systems, common is injection of an alkalizing amine (formerly known as neutralizing amines) or amine blend to the boiler feedwater. This provides protection directly within the feedwater system, but where volatilization of some amine with steam will carry over to the condensate return. Figure 8 lists the most common alkalizing amines.

These compounds have different volatilities, so, depending upon the application, products can be blended to allow somewhat selective carryover to steam. The chemicals will re-dissolve in the condensate to help protect condensate-return systems.

Note: Feedwater chemistry for high-pressure utility boilers is quite different than the examples outlined above. Unless the feedwater system contains copper alloys (virtually non-existent in combined cycle HRSGs), oxygen scavengers and complete deaeration are not recommended. Rather, modern feedwater treatment programs require a small D.O. residual. Also, ammonia is the choice for feedwater pH control, as alkalizing amines will decompose in superheaters/reheaters to form unwanted small-chain organic acids and carbon dioxide. References 1 and 3 provide detailed information regarding this chemistry, a primary purpose of which is to minimize flow-accelerated corrosion (FAC).

Film-Forming Chemistry

Space limitations prevent an in-depth discussion of film-forming chemistry, but the concept is re-emerging for power and industrial plants. As the name implies, film-forming products (FFPs) are designed to establish a protective layer on metal surfaces during normal operation and down times.

FFPs have been utilized in a variety of applications for years, including steam generation, but difficulties (formation of sticky deposits, colloquially known as “gunk balls”) led to disuse in the power industry. New, more specialized products have emerged that are showing success in some applications. They can be separated into two general categories.6

- Amine based filming products (AFP)

- May be blended with neutralizing amines or contain just the active filming agent.

- Non-amine based filming products (NFP)

- Contain no neutralizing or filming amines.

A critical point to remember is that FFPs are a supplement to, not a replacement for, good chemistry practices that have been developed over the last century.

FFP chemistry will be a major focus at the annual Electric Utility & Cogeneration Chemistry Workshop (EUCCW), which will be co-locating with POWERGEN 26 in San Antonio in January. More information is available at www.powergen.com. Please plan to join us to learn more about these important developments.

Disclaimer

This article offers general information and should not serve as a design specification. Every project has unique aspects that must be individually evaluated during project design and subsequent operation. From those evaluations, comprehensive specifications can be developed and adjusted per operating data.

References

- International Association for the Properties of Water and Steam, Technical Guidance Document: Volatile treatments for the steam-water circuits of fossil and combined cycle/HRSG power plants (2015). IAPWS technical guidance documents can be downloaded at no charge from www.iapws.org.

- International Association for the Properties of Water and Steam, Technical Guidance Document: Phosphate and NaOH treatments for the steam-water circuits of drum boilers of fossil and combined cycle/HRSG power plants(2015).

- Guidelines for Control of Flow-Accelerated Corrosion in Fossil and Combined Cycle Power Plants, EPRI Technical Report 3002011569, the Electric Power Research Institute, Palo Alto, California, 2017. This document is available to the industry as a free report because FAC is such an important safety issue.

- Buecker, B., “Condenser Chemistry and Performance Monitoring: A Critical Necessity for Reliable Steam Plant Operation”; proceedings of the 60th Annual International Water Conference, October 18-20, 1999, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

- Buecker, B., and Shulder, S., Power Plant Cycle Chemistry Fundamentals”; pre-workshop seminar for the 35thAnnual Electric Utility Chemistry Workshop, June 2, 2015, Champaign, Illinois.

- Buecker, B., and Shulder, S., Combined Cycle and Cogeneration Water/Steam Chemistry Control”; pre-workshop seminar for the 40th Annual Electric Utility Chemistry Workshop, June 7, 2022, Champaign, Illinois.

- Flynn, D.J., ed., The Nalco Water Handbook, Third Edition, McGraw-Hill, 2009.

Brad Buecker

Brad Buecker currently serves as Senior Technical Consultant with SAMCO Technologies. He is also the owner of Buecker & Associates, LLC, which provides independent technical writing/marketing services. Buecker has many years of experience in or supporting the power industry, much of it in steam generation chemistry, water treatment, air quality control, and results engineering positions with City Water, Light & Power (Springfield, Illinois) and Kansas City Power & Light Company's (now Evergy) La Cygne, Kansas, station. Additionally, his background includes eleven years with two engineering firms, Burns & McDonnell and Kiewit, and he spent two years as acting water/wastewater supervisor at a chemical plant. Buecker has a B.S. in chemistry from Iowa State University with additional course work in fluid mechanics, energy and materials balances, and advanced inorganic chemistry. He has authored or co-authored over 300 articles for various technical trade magazines, and he has written three books on power plant chemistry and air pollution control. He is a member of the ACS, AIChE, AIST, ASME, AWT, CTI, and he is active with Power-Gen International, the Electric Utility & Cogeneration Chemistry Workshop, and the International Water Conference. He can be reached at bueckerb@samcotech.com and beakertoo@aol.com.

Related Articles

The 7 Secrets of Pump Reliability

Leaky Shaft Seals

Matching a Hydraulic Motor to the Load

MEMS Accelerometer Performance Comes of Age

How Water Causes Bearing Failure

Preventive vs. Reactive Maintenance Part 4: Steam Generation Series