My Maintenance – Why Settle for RCM Alone?

Dave Porrill

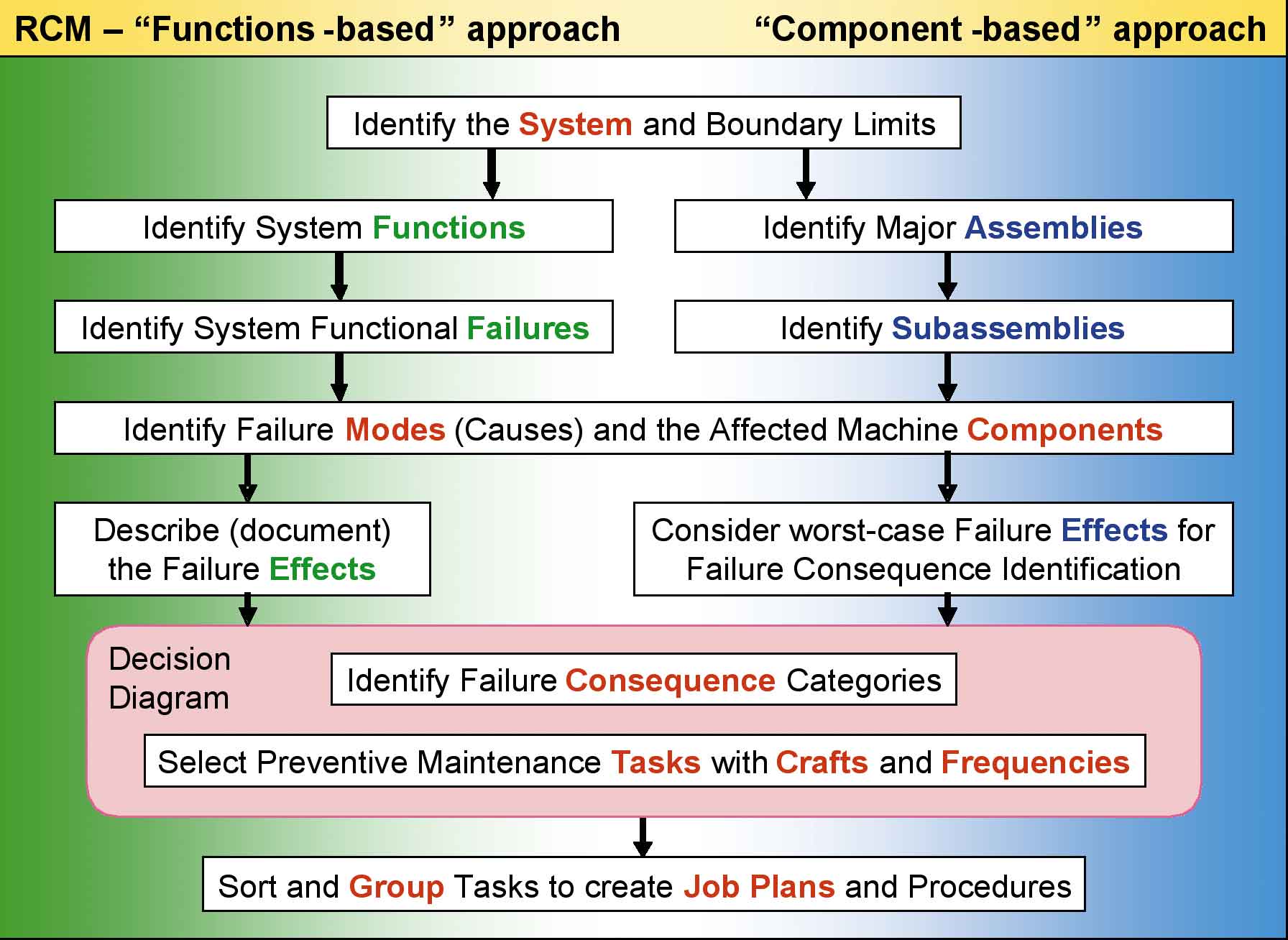

Perhaps the most celebrated analytical technique is RCM which has been around since the pioneering days of Nowlan and Heap (1978) and which in later years was presented to land-based industries by Moubray as RCM2. Then there are a multitude of variations to this central philosophy which have been designed based on the argument that “Classical RCM” is too time-consuming to be practical. Some of these alternative approaches are closely aligned to the original philosophy, but regrettably, there are also some which are so vastly different that they lose all resemblance to anything remotely useful for developing equipment maintenance routines! In an attempt to terminate any further debate, the Engineering Society for Advanced Mobility, Land, Sea Air and Space, International (SAE) published a document titled “Evaluation Criteria for Reliability-Centred Maintenance (RCM) Processes” (JA1011). This document describes the criteria that must be met in order to refer to a maintenance analysis as “RCM.” It is important to note however, that just because a particular form of maintenance analysis does not meet the criteria spelled out in JA1011, it does not mean that it is not a valid analytical methodology; it simply means that the term “RCM” should not be applied to it. If we consider that RCM evolved out of the airline industry, and RCM2 was largely an attempt to adapt the philosophy to land-based industries, it is not surprising that there will surely be circumstances where the details of RCM may feel like an uncomfortable fit in the context of a production site. For example, the criteria that are important in a nuclear power station may be noticeably different from a fruit juice factory. Similarly, the operating context of a national rail network is quite different from a factory producing electronic circuit boards for the computer industry. It must be acknowledged therefore, that the nuances and idiosyncrasies of different industrial organisations would benefit from allowing a certain amount of flexibility in the way they develop their preventive maintenance routines.

Related Articles

Proactive Maintenance for Hydraulic Cylinders