Lathered in Valor: Saluting the Maintenance Heroes of Operation Ivory Soap

Natalie Johnson

Posted 06/14/2023

Overlooking the Mobile Bay, a cannon can be heard firing each day. Guests of the Grand Hotel in Point Clear, Alabama may know it’s to honor members of our armed forces. What most don’t know is that they are sleeping in the same rooms as soldiers during World War II, training for a secret mission. In 1942, U.S. aircraft began flying long and difficult bomb raids over Japan in the Pacific Theatre. The planes returned, beat up by enemy fire and in desperate need of maintenance and repair. The Army considered building land-based repair depots, but these would take too much time. The solution was retrofitting cargo ships and converting 5,000 soldiers to sailors in order to return fighter jets back to combat as soon as possible. Operation Ivory Soap wasn’t declassified until 1953 and the bravery and skills exemplified by these soldiers has gone largely unrecognized, except at the Grand Hotel where it all began.

In 1944, Colonel Matthew Thompson rented the entire Grand Hotel in Alabama for $1 per year and a promise. The Army needed to find a training center near the water as Army technicians were required to acquire marine survival skills before boarding the vessels. Colonel Thompson heard the hotel was considering a temporary closure due to the state of the country. He inquired about leasing the space for training, but the owner, Ed Roberts, refused.

Roberts was too old to join the service and felt lending his hotel to the Army was his contribution to the war effort. His only request: don’t wear boots on the new hardwood floors!

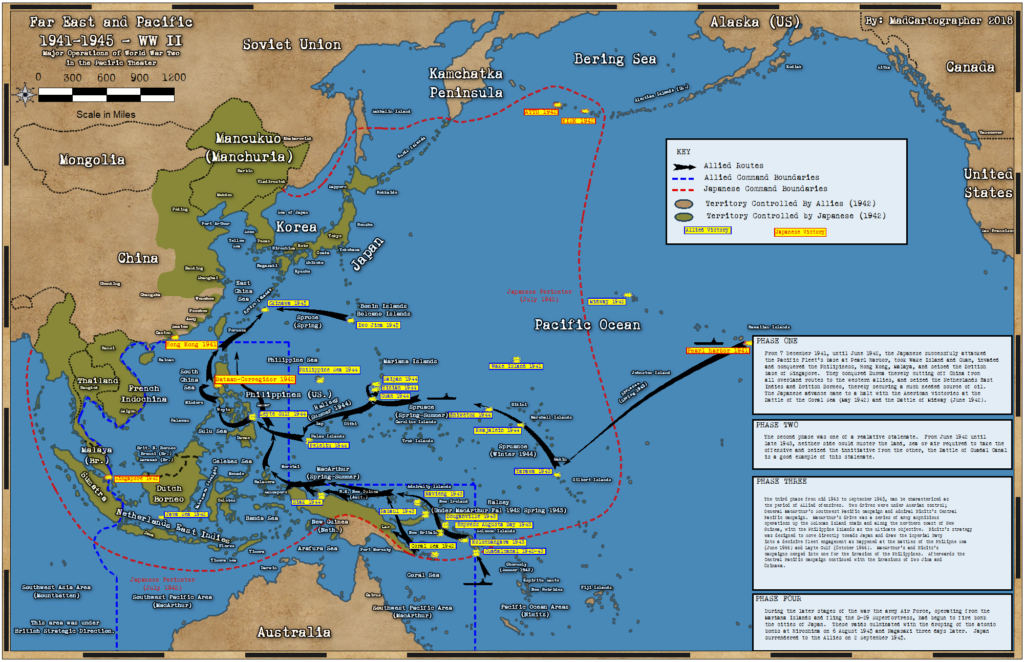

Island Hopping

‘Island hopping’ was a tactic deployed by the allies in WWII. When trying to capture islands in the Pacific, the allies decided to pass up the heavily fortified enemy isles and capture the surrounding islands. This strategy allowed the allies to utilize the element of surprise and move quickly through the Pacific towards the Japanese mainland. As they began to capture other islands, the remaining ones would eventually “wither on the vine.”

Once an island was captured, the allies could use its airfield and extend their presence in the Pacific moving closer to Japan. But after successfully capturing several islands, they still had a persistent problem. American bombers and fighter planes returning from missions needed maintenance and repairs, but there wasn’t an ideal spot to set up shop in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Earlier in the war, the Army had considered an alternative to land-based repair depots and large maintenance facilities, as moving these could take up to 6 months. Now was the time to enact this plan and create multiple floating aircraft repair shops.

Floating Aircraft Repair Shops

Operation Ivory Soap began in Alabama: Twenty-four cargo ships were delivered to Mobile, Alabama in the Spring of 1944 to be stripped and converted to floating maintenance and repair shops. Six liberty ships measuring 440 feet required a crew of 344, while the eighteen smaller auxiliary vessels were 187 feet and only required 48 sailors.

The larger ships were converted into Aircraft Repair Vessels and the smaller ships were retrofitted to operate as Aircraft Maintenance Vessels. Equipped with machine shops and the latest machine tools, all vessels could support the maintenance and repair of B-29 bombers, P-51 Mustangs, Sikorsky R-4 helicopters, and amphibious vehicles.

Machine shops were added to allow for sheet metal- wood- and electrical work, painting, and fabrication. Air-conditioned camera and instrument shops were added as well as a shop designed to generate the oxygen used aboard bombers. Two of the shops were even equipped to support B-29s through radar and central fire control system repair.

To aid amphibious operations, the liberty ships were equipped with two motor launches, two LCVPs, two DUKWs, and steel decks to support helicopters for ship-to-shore transportation. The only work the ships couldn’t handle was engine overhaul, due to limited space.

Some of the equipment carried onboard these floating maintenance and repair hubs:

- Machine tools

- Welding

- Cranes

- Radiator

- Sheet Metal

- Wood

- Blueprints

- Patterns

- Aircraft dope

- Electrical Equipment

- Paint

- Air-conditioned instrument and camera shops

- Batteries

- Radios

- Propellers

- Tires

- Armament and turrets

- Fuel Cells

- Radar

- Carburetors

- Plating

- Turbosupercharger

In addition to their maintenance facilities, each ship had a mess hall, sleeping quarters, orderly room, laundry facilities, exchange, hospital, brig, and even a post office. The physical ship conversions equipped the vessels with everything needed to repair aircraft and keep the crew healthy. In addition to the renovations, the names of each vessel were also changed. The Liberty ships were nicknamed “the generals” and the auxiliary vessels “the colonels” as each ship was named after a respected General or Colonel in the Army.

Training in the Mobile Bay

While the ships were being retrofitted, Colonel Matthew Thompson was tasked with transforming soldiers into sailors. With less than two weeks to organize and begin the training program, Colonel Thompson went right to work.

He began his recruiting efforts at Brookley Army Airfield near Mobile, Alabama. The base had a highly skilled workforce and was a major supply base for the Air Technical Service Command, a unit responsible for the distribution, installation, and repair of mechanical airborne equipment.

Once 5,000 soldiers were selected they were transported to the Grand Hotel, which housed soldiers and served as a maritime training facility; floors were referred to as decks, the dining room was the mess hall, time was kept by a ship’s bell, and tobacco use was only permitted when the smoking lamp was lit. The Colonel even had a 40-foot tower erected so sailors could learn to abandon ship.

The soldiers, primarily Army Air Force officers, mechanics, and machinists, were being transformed into seamen as they learned to swim in the hotel pool and abandon ship in the Bay. They had to learn the basics: knot-tying, marching, ship identification, drill navigation, signaling, cargo handling, ship orientation, sail making, amphibious operations, and more. Two men from each ship were also trained to be divers.

The soldiers displayed impressive intellect and strength as they completed grueling training in the Alabama summer heat to transform themselves into sailors. Once they completed their training others in the military nicknamed them “saildiers” (sail-jers) as they wore Army uniforms on land and Navy dungarees with white hats aboard ship.

One night, while Colonel Thompson was working, a “saildier” approached him and said, “I’ve got a name for the mission: Ivory Soap.” He came up with the idea in the shower, based on the one thing ivory soap and aircraft repair units have in common: they float. The name stuck and Operation Ivory Soap was officially underway.

Launch Day

Manned by members of the Army, Navy, and the Merchant Marines, the first floating aircraft maintenance and repair unit was deployed in October of 1944. By February all vessels had traveled through the Panama Canal to the Pacific Ocean and reached their destinations: Marshall Island, the Northern Mariana Islands, Iwo Jima, Luzon, Guam, and Okinawa. Each ship carried anti-aircraft guns manned by members of the naval armed guard.

With the ships in place, the newly trained sailors were equipped with all supplies necessary to mend aircraft. Anything that could be damaged, could be repaired on these vessels – from your wristwatch to the wing of a fighter jet. Crews worked 24 hours a day to overhaul anything that might need repair. If they didn’t have the spare part, they could manufacture one utilizing the large inventory of steel, aluminum, and other materials.

Mechanics took the DUKW vehicles or helicopters to shore to inspect damaged aircraft. Small parts were transferred to the ship for repair by helicopter and larger parts transported by the DUKW vehicles. If they had to repair the aircraft in the field, mechanics could also set up shop on shore to complete repairs.

In addition to transporting mechanics, the Sikorsky R-4 helicopters onboard were used to locate downed planes, rescue flight crews, and transport spare parts.

First Lt. Daniel A. Nigro, a helicopter pilot during the war recalled him and his comrade John Halpin flew repair personnel to airstrips and returned with spare parts even when they exceeded the helicopter’s weight capacity. He told Air Corps Magazine how they stripped their Sikorskys “We did anything – even taking off the copter doors to lighten our load.”

Nigro, Halpin, and their comrades’ ingenuity were crucial to operations in the Pacific. Hundreds of bombers and fighter jets returned to battle to continue fighting because of the mechanics and technicians’ onboard maintenance and repair vessels. Between November 1944 and September 1945 one vessel, Major General Herbert A. Dargue, supplied over 38,000 spare parts and units to repair B-29s and P-51s ranging from spark plugs to the central fire controls.

Aircraft taking off from these vessels flew continuous missions over Japan, making the maintenance efforts key to strengthening the allies position in the Pacific Ocean. Not only did the maintenance and repair crews service hundreds of aircraft, they saved thousands of lives.

Operation Ivory Soap was omitted from the book, “The Army Air Forces in WWII” as it wasn’t declassified until 1953. The bravery and skills exemplified by these ‘saildiers’ has gone largely unrecognized, except for where the story began. Everyday around 4pm guests still gather at the Grand Hotel to look over the Mobile Bay and honor members of our armed services with a cannon firing and resounding salute. The maintenance and repairs performed on the retrofitted vessels were crucial for the final push in the Pacific, thankfully the pool at the Grand Hotel was available to convert these incredible maintenance workers into sailors allowing their skills to be utilized in the middle of the Pacific.

Speaking of Aircraft Repair and Maintenance, there is a current shortage.

Read more: Critical Gaps in the Sky: The Looming Aviation Maintenance Technician Shortage

Midweek with Maintenance World

Looking for a midweek break? Keep up with the latest news brought to you every Wednesday by the Maintenance World crew.

Natalie Johnson

Natalie Johnson is the previous editor/website administrator for MaintenanceWorld.com, and is currently a student at Campbell University Norman Adrian Wiggins School of Law.

Related Articles

Cardinal Manufacturing, Helping to Bridge the Manufacturing Skills Gap

South Carolina Ranked as the #1 State for Manufacturing

The Decade of American Reshoring

Lost Radioactive Capsule Proves Preventive Maintenance is as Important as Ever

HBD Condition Monitoring Devices at the center of Ohio Derailment

Failure Analysis Uncovers the Cause of the Keystone Oil Spill