3 Techniques for Optimizing Preventive Maintenance

John Natarelli, T.A. Cook

John Natarelli presents 3 Techniques for Optimizing Preventive Maintenance

When Benjamin Franklin wrote, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” he was referring to fire safety. But, as you may know from experience, this saying holds true with regard to preventive maintenance (PM). Simply stated, preventive maintenance is an activity performed at a set interval to maintain an asset, regardless of its current condition. It’s a properly planned activity, where materials and parts are on hand and labor is scheduled ahead of time.

The goal of any PM program is not only to extend the life of an asset or maintain it to its existing capabilities, but to also identify potential failures that could cause an unexpected event in the future. Properly planned corrective maintenance is typically several times less expensive than performing unplanned work. But, are the typical frequencies that PMs occur actually correct?

The Society for Maintenance and Reliability Professionals (SMRP) Best Practices Committee recommends approximately 15 percent of total maintenance labor hours be associated with PM work. This, of course, could fluctuate depending on the type of plant, its location, age and complexity, among other things. However, having a line in the sand can provide a starting point to begin optimizing preventive maintenance.

Though there are many potential starting points, one option is to begin by evaluating the amount of emergency work that occurs on equipment that regularly gets PM performed on it. Start by identifying a critical plant process and its associated assets. Once these assets are identified, choose one piece of equipment that gets a regular PM. Do not pick the most complex PM, as you may be immediately overwhelmed with the amount of information available. Instead, choose something basic. Begin by tallying the amount of PM labor hours and emergency labor hours charged to this specific piece of equipment over a period of time, for example, three to five years to start with. If the site has properly utilized a computerized maintenance management system (CMMS), this task should be relatively easy, as all maintenance work performed should be available. If a CMMS has not been adequately utilized, this task may be more time consuming.

Once this information has been gathered, compare the amount of labor hours charged to PM work versus the amount charged for emergency work. If the emergency labor value is greater than that spent on completing PMs, something is probably wrong. It could be that the work within the PM is focused on the wrong item and missing something that’s having a frequent impact to production. Root cause analysis on failures must be performed to completely understand this. Generally speaking, if the numbers are adverse and emergency labor is consistently minimal or nonexistent, the frequency of PMs might be adequate.

There is also the possibility that PMs are being performed at the wrong interval even though hours are aligned as previously explained. John Day, Jr., manager of engineering and maintenance at South Carolina’s Alumax, the first organization in the world to be certified compliant with world-class standards, developed another method to evaluate PM effectiveness. Day’s theory assumes that for every six PMs performed, one corrective work order that cannot be completed within the required PM time frame should be written. If the ratio is greater than 6:1, say 10:1, then it’s likely the PM is being completed too frequently. If the ratio is less, at 2:1 for instance, then the interval between PMs is likely too great, resulting in corrective work orders being written once for every two times the PM is performed. Again, utilizing a CMMS will make gathering and evaluating this information a much easier task.

Considering every corrective work order could eventually lead to unplanned downtime, should the frequency of the PM in the last example be increased? Maybe, but not without some additional research. It is important to understand the work that was identified, the threat it poses and the asset that it’s on. If the corrective work poses a higher risk, the frequency should be increased. However, a conservative approach should be used to begin with. Also consider instead of every year, changing the frequency to every nine months. However, if the work poses no threat to safety or production loss, it is quite possible it’s an acceptable risk that can be addressed as it is identified. The bottom line is that without a consistent evaluation process, the optimal frequency cannot be accurately determined. And, as mentioned earlier, variations in plant operating conditions also can impact the decision.

A third way to begin the PMO process is perhaps the easiest and the most overlooked. It’s that of the human factor – the craftspeople performing the work. As plants, and the workforce itself, are aging, it is highly likely that the PMs being performed were established many years ago and never revalidated. It’s also likely that the same people perform the same PM every time it’s scheduled. An engaged maintenance workforce can be a tremendous help in the PMO process. They’re the ones who can provide input on its quality and contents. Since they routinely perform the work, they can help identify process improvements and validate that the PM includes all relevant work. They can make suggestions on items that should be added to or removed from the PM and could even provide input as to the right frequency.

Each of these three techniques provides a starting point for optimizing preventive maintenance. Additional methods, such as utilizing metrics like mean time between failures and mean time between maintenance, also can provide benefits. Whichever path you choose, remember that optimizing preventive maintenance is a facet of the continuous improvement process. The SMRP’s 15 percent guideline and Day’s 6:1 ratio may not be a perfect fit for every plant or asset, but they’ll provide a starting point for a PMO initiative.

A vision and a long-term commitment from every level of the organization are required for PMO to succeed. Achieving small gains early on can provide momentum and increase buy in to the process over the long haul. And although the process may initially seem costly, optimizing preventive maintenance can reap benefits for years to come.

John Natarelli

John Natarelli is a Project Manager for T.A. Cook. While based in North America, he has managed projects for refining leaders in both the United States and Canada. John has over eleven years of consulting experience and has worked on projects across a range of different industries, with the last four years dedicated to the oil and gas industry.

Related Articles

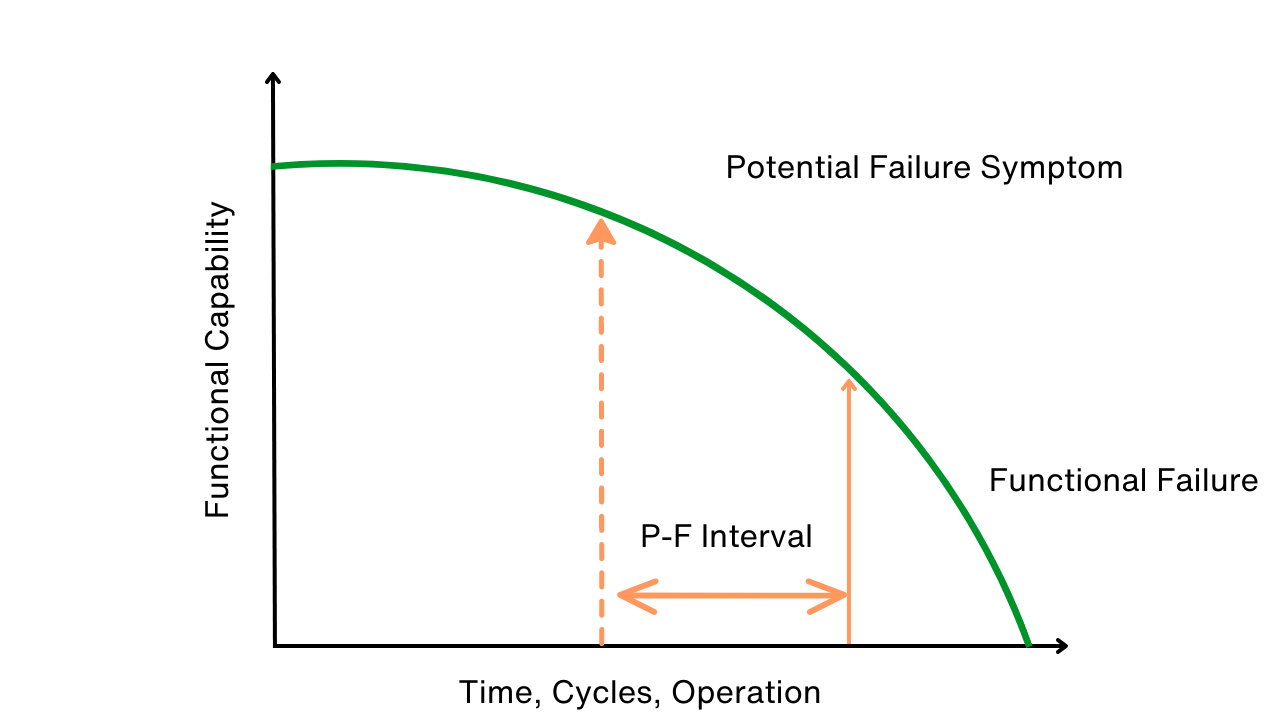

Use P-F Intervals to Map, Avert Failures

The RCM Trap

Can You Really Justify Reliability Centered Maintenance (RCM)?

Design for Maintainability