Setting Disciplined Priorities when Prioritizing Maintenance Work

Christer Idhammar, IDCON INC

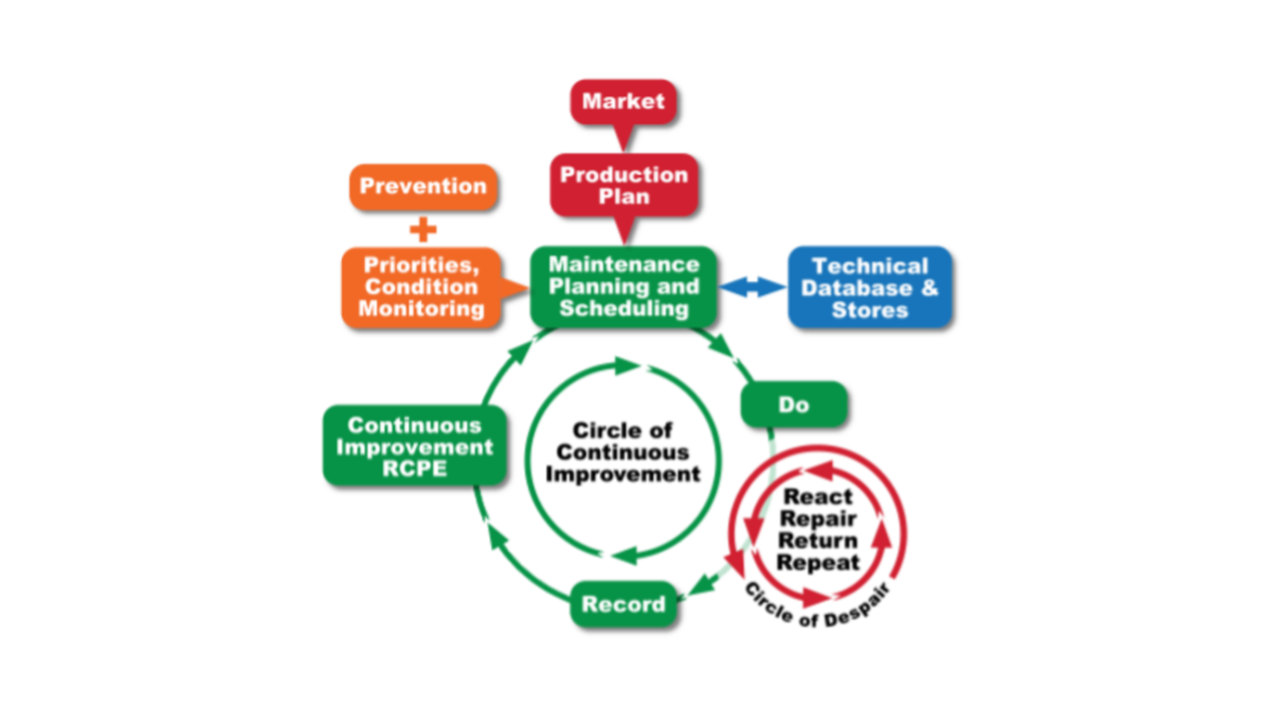

A Maintenance Planning and Scheduling Perspective

Priority, as defined in the Franklin Dictionary, means “coming before in time, order, or importance.” When prioritizing maintenance work, one must consider its importance to the entire company in question. My experience shows that, in the real world of most maintenance departments, you can classify priorities in two groups: Emotional priorities and real priorities.

Emotional Priorities

An emotional priority is one that is based on feelings instead of objective judgment of importance. The importance of the maintenance work is judged only as it relates to the production area where the requester works.

For example, a person in operations might want to have a maintenance job done just to get it off of his or her mind. It is common to see that many of these types of priorities are requested using a standing work order number or are requested verbally, bypassing the use of a computerized or manual maintenance work request routine.

Because maintenance acts as service to operations, these methods of requesting maintenance work will continue to increase if written work requests and strict disciplines for standing work orders are not enforced. This happens because it is more convenient for the requester to have someone else document the work request than to do it himself.

Another reason why emotional priorities are common is that they often provide the only way to get a maintenance job done within a reasonable time frame. Requesters of work know when everybody in the organization is abusing the priority system.

They also know that if they try to be nice and instate a lower priority than is necessary, their specified job will never get done. Ultimately, this means that the work request will be pushed through with a higher priority than necessary.

Jobs with emotional priorities, as well as true emergencies, will bypass the planning and scheduling process and consequently cost more money.

Real Priorities

What I call “real priorities” are based on the importance of the work to be done and its benefit for the whole company or production area.

The priority of the work is based on the consequence of not doing the job and the condition of the component as measured during a component inspection. In a good organization, up to 90% of all maintenance work is a result of condition monitoring, including basic inspection routes and interviews with operators. With real priorities, more work can be planned, and after that it can be scheduled and executed in an efficient way.

A Source of Conflict

Requesters of maintenance work often have only their own production area in mind when prioritizing maintenance work, while their maintenance partners are often faced with ten “priority one” jobs from different requesters when they can only accommodate five.

This results in conflict with the people who don’t get their jobs performed. And to make matters worse, it is often the people who give the maintenance planner or supervisor the most problems if their jobs are not done who get precedent.

This is often done at the cost of others who might have had a more real need for a completed job.

Confronting the Problem

I know that many readers recognize the type of conflict I have described as if it had been taken from their own mills.

So what can you do about improving it?

I like to offer the following actions for changing the state of the maintenance process from being reactive to being planned, scheduled, and controlled:

- Set up a task force between operations and maintenance with the objective of arriving at more disciplined priorities.

- Educate key people about the importance of using the right priorities. Teach them that it costs several times more to do a job that breaks into a set schedule than to do a job that is planned and scheduled.

- Agree that operations and maintenance will decide priorities together according to well-defined guidelines. The only jobs that justify a “priority one” (immediate action that breaks into other ongoing jobs) are jobs such as the following:

Immediate risk for personal injury or environmental damage

Production line is down, and, for example, there are no buffers of paper to keep a coater running until the job is performed.

Immediate risk for production loss or high maintenance costs

All other jobs, which should be included with examples in the priority guidelines, should be prioritized with a requested date for latest completion. For example, if a pump that has back up fails, it will not automatically constitute a “priority one” job.

Determining and using new priority guidelines will yield faster results with fewer breaks in work and increase the planning, scheduling, and control of maintenance. However, count on the fact that even this simple process of implementing guidelines might take time

Maintenance Planning and Scheduling Book by IDCON

Maintenance Planning and Scheduling training and Implementation Support by IDCON.

Christer Idhammar

Christer Idhammar started his career in operations and maintenance 1961. Shortly after, in 1985, he founded IDCON INC in Raleigh North Carolina, USA. IDCON INC is now a TRM company. Today he is a frequent key note and presenter at conferences around the world. Several hundred successful companies around the world have engaged Mr. Idhammar in their reliability improvement initiatives.

Related Articles

No other element of the technical database provides as much value to planning as an accurate bill of materials. Bills of material are a list of parts that are used on the equipment. When developing BOMs, focus on parts used for routine maintenance, repair, and operation of the equipment. Individual parts should contain a minimum amount of information including: a consistent and organized name, manufacturer and their item number, price, lead time, and quantity needed for the equipment.

No other element of the technical database provides as much value to planning as an accurate bill of materials. Bills of material are a list of parts that are used on the equipment. When developing BOMs, focus on parts used for routine maintenance, repair, and operation of the equipment. Individual parts should contain a minimum amount of information including: a consistent and organized name, manufacturer and their item number, price, lead time, and quantity needed for the equipment.

See More

Historically, maintenance textbooks have defined a shutdown as "an unplanned equipment failure event that causes an operational production line, process, area or section of a plant to be temporarily turned off or closed for emergency repair, and resumed to operational status immediately following the repair of the failed equipment." Turnarounds are defined as "a planned event that required the closure of an entired operational plant or facility to perform one or many pre-planned technology or system upgrades, equipment upgrades, and maintenance restorations, within a defined time period."

Historically, maintenance textbooks have defined a shutdown as "an unplanned equipment failure event that causes an operational production line, process, area or section of a plant to be temporarily turned off or closed for emergency repair, and resumed to operational status immediately following the repair of the failed equipment." Turnarounds are defined as "a planned event that required the closure of an entired operational plant or facility to perform one or many pre-planned technology or system upgrades, equipment upgrades, and maintenance restorations, within a defined time period."

See More

The work process we call maintenance planning can almost always be improved in any given mill or plant. In fact in most plants we visit maintenance planners don’t plan. Planners do all kinds of tasks except work order planning.

The work process we call maintenance planning can almost always be improved in any given mill or plant. In fact in most plants we visit maintenance planners don’t plan. Planners do all kinds of tasks except work order planning.

See More

ONCE UPON A TIME in a maintenance department, a work order woke up in the morning, feeling very lazy, unable to open his eyes or get up to walk. It's been a long time for him in the same room, nobody knocks on the door to say hello, how are you, or to release him so he can show his presence. He looks in the mirror and finds he has changed a lot since being created and kept in the backlog. Looking at gray hair covering his head, he tries to remember his lifecycle since that day when he became a pending order waiting for spare parts to arrive. This spurred his friends to give him the nickname, "Nomat."

ONCE UPON A TIME in a maintenance department, a work order woke up in the morning, feeling very lazy, unable to open his eyes or get up to walk. It's been a long time for him in the same room, nobody knocks on the door to say hello, how are you, or to release him so he can show his presence. He looks in the mirror and finds he has changed a lot since being created and kept in the backlog. Looking at gray hair covering his head, he tries to remember his lifecycle since that day when he became a pending order waiting for spare parts to arrive. This spurred his friends to give him the nickname, "Nomat."

See More

While working this April in Holland, I saw a plant utilizing a marvelous Dutch phrase: "Ja, maar", which means "Yes, but ..." Seeing it first-hand helps me understand a principle of successful planning. Many plants can't implement successful planning because they assign the planners many worthwhile activities that are not planning. "Yes, planning is supposed to really help us, but we need the planner to do this other thing that really helps us." Ja, maar.

While working this April in Holland, I saw a plant utilizing a marvelous Dutch phrase: "Ja, maar", which means "Yes, but ..." Seeing it first-hand helps me understand a principle of successful planning. Many plants can't implement successful planning because they assign the planners many worthwhile activities that are not planning. "Yes, planning is supposed to really help us, but we need the planner to do this other thing that really helps us." Ja, maar.

See More

Since there has been tremendous progress in planning and scheduling in the process industry during the last 20 years, it might be worthwhile to give an overview of the current state-of-the-art of planning and scheduling problems in the chemical process industry. This is the purpose of the current review.

Since there has been tremendous progress in planning and scheduling in the process industry during the last 20 years, it might be worthwhile to give an overview of the current state-of-the-art of planning and scheduling problems in the chemical process industry. This is the purpose of the current review.

See More

Underground mining operations, similar to many industrial enterprises, have long recognized the potential benefits of maintenance planning. However, underground mining operations’ efforts to implement maintenance planning have generally met with little success. One finds that after an initial period of enthusiastic support implemented systems and procedures fall to disuse. Most companies, upon the collapse of their maintenance planning, convince themselves that underground mining is so "unique" that to accurately plan, schedule and measure maintenance work is impractical.

Underground mining operations, similar to many industrial enterprises, have long recognized the potential benefits of maintenance planning. However, underground mining operations’ efforts to implement maintenance planning have generally met with little success. One finds that after an initial period of enthusiastic support implemented systems and procedures fall to disuse. Most companies, upon the collapse of their maintenance planning, convince themselves that underground mining is so "unique" that to accurately plan, schedule and measure maintenance work is impractical.

See More